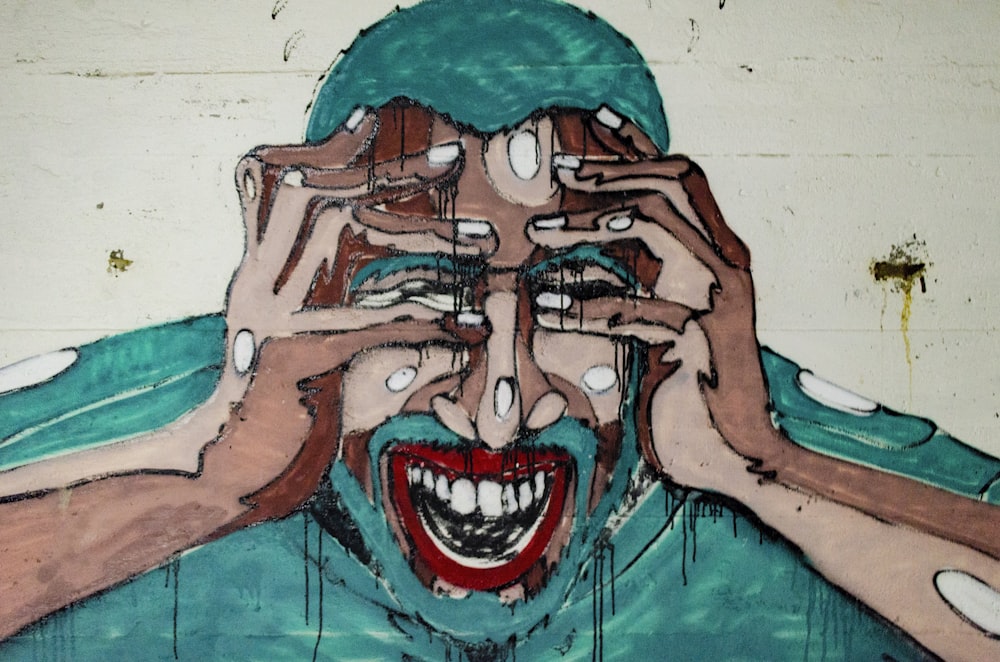

In the ever-quickening pace of modern life, stress is an ever-present factor.

Stress is one of the most important risk factors for mental and physical health in developed countries, increasing the incidence of mental illness and mortality. Two thirds of the working population suffer from stress or time pressure, with 38% of women and 21% of men experiencing severe physical symptoms due to stress.

Stress seems to be an unavoidable byproduct of modern lifes, decreasing our quality of living and costing our economies billions.

The message rings clear: stress is bad. But is that really the full picture? Stress has evolved for a reason, and it can give us adaptive advantages for dealing with challenging tasks. In this article we will explore what stress is, why some people can cope with it better than others, and how fascinating new research shows that the way we think about our stress has a big influence on how unhealthy it actually is.

What is stress?

To lay some groundwork, we first need to establish what we are talking about. Stress is used to describe an almost infinite number of human experiences. It is used both in science and colloquially for many different processes. We experience acute stress when we lose our job, divorce from a spouse, or are in a physical confrontation, but we can also experience long term latent stress depending on life contexts, such as growing up in poverty or being unhappy in our jobs. Triggers for stress are called “stressors”, while stress can also be used more generally to refer to the cognitive, emotional, and biological “stress responses” that such situations elicit.

The most widely adopted traditional psychological definition of stress comes from Lazarus and Folkman (1984). According to them, stress is the result of an interaction between the individual and the environment. An event triggers stress when the individual appraises a particular situation as dangerous or hurtful and evaluates their own resources as insufficient to cope with the situation. The appraisal process of Lazarus’s transactional stress model occurs in several stages. In the first stage, the affective significance of the situation is assessed. Is the event a threat or is it irrelevant? The search for available coping strategies and the evaluation of their expected effects follows in the second phase. In the third phase, the so-called reappraisal phase, a new assessment of the situation is taking the expected coping options and effects into account. Based on this reappraisal, coping can be activated or reduced.

This stress and coping transaction process therefore understands psychological stress as a stimulus-related emotional response to threats in the environment. Hence our experience of stress crucially depends on our appraisals of our life situation, tying it up with our personalities and mindsets.

The impact of personality and mindset on stress

The five-factor model of Costa and McCrae (1997) is the most recognized model of personality typology. It distinguishes the categories neuroticism, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience. Goldberg (1981) referred to these as the Big Five.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, neuroticism predicts exposure to interpersonal stress and a tendency to appraise events as highly threatening and coping resources as low. If this is paired with low conscientiousness, this leads to particularly high stress exposure and threat appraisal. On the opposite end of the spectrum, low neuroticism with high extraversion predicts low experiences of stress. Outgoing people that aren’t afraid of anything aren’t very easy to stress out.

Our personality can also modulate our behaviors, which in turn affect our experience of stress: conscientious individuals plan ahead for predictable stressors and avoid impulsive actions, saving them a lot of unnecessary headache, while agreeable people avoid interpersonal conflict and its associated social stress.

Not only our behavior, but our mindset can affect how we experience stress and how harmful it is for our health. As Dr. Alia Crum from Stanford points out, the experience of stress when pursuing goal related efforts is not necessarily debilitating, but can even enhance our ability to perform. Stress doesn’t only make us respond to threats, it also helps us respond to challenges and opportunities. Extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness can all relate to perceiving events as challenges rather than threats and positively trigger coping resources. Studies show that re-framing of stressors as challenges can in turn lead to more adaptive outcomes.

On a more fundamental level, the way we view stress itself influences the effect it has on us. Correlational studies show that people that think of stress as enhancing productivity also observe better health outcomes and higher performance. Especially in high-performance environments like the Navy SEALs where stress is a daily companion, this mindset is much more widespread.

Going beyond correlation, intervention studies that used educational video clips to actively orient people’s perception of stress as either positive or negative lead to changes in their mindset and, in turn, to significant positive changes in performance and health outcomes.

This doesn’t mean that stressors are always good, or that our societies don’t need to adapt in other ways to minimize unnecessary stressors in people’s lives by changing work culture and reducing crime. But perceiving stress as enabling can open the door to realizing positive outcomes and can in turn lead to more fruitful actions.

These insights are important given that the public health message around stress is dominated by a negative mindset, and the negative effects of stress are extremely detrimental for our societies at large. If we can change these outcomes by changing the messaging, it is a first step to achieve a society less dominated by stress.

This article was co-written by Mara Römer and Manuel Brenner.

About the Author

Mara Römer completed her bachelor’s degree in psychology as a major and business administration as a minor and is now in her master’s in psychology. She is currently writing her master’s thesis in geronto-psychology and focuses on the topics of resource activation in old age, retrospection of life, and healthy aging. She cares about the health and well-being of others. At ACIT she is a Senior Marketing Manager. Everything you see on ACIT’s social media and newsletter is from her. Besides ACIT and her studies, her passion is the not so well known sport “Aerial Hoop”.