While ACIT is an organization about critical thinking and science, we believe that the boundaries of art and science don’t always need to be so clear cut. That’s why we wanted to take up the opportunity of Beethoven’s 250th birthday year to publish an article about this slightly unusual topic.

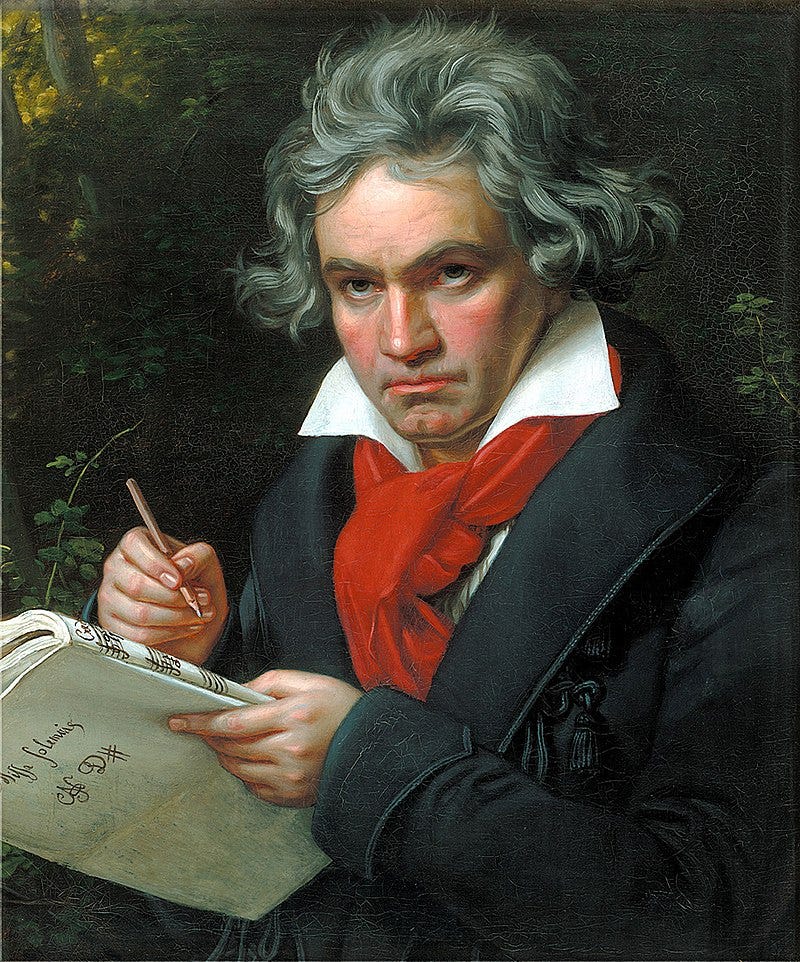

On the genius of Ludwig van Beethoven

It seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce…

We write the year 1802, and twenty-nine-year-old Ludwig is staying, far removed from the bustle of society, in a peaceful country home close to Vienna. The environment might be calm and beautiful, but he is not well. His hearing has been getting worse for the past three years.

It started out with a ringing in his ears, which did not go away again on its own but got increasingly louder and louder.

And then his hearing begins to suffer. Much of it is gone by 1802.

Fate has played a particularly cruel trick on him. Ludwig is a musician, a composer. Music is his life, and hearing is his livelihood.

He contemplates suicide. On October 6th, 1802, he writes a farewell letter to his brothers.

‘O ye men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do ye wrong me, you do not know the secret causes of my seeming… I was compelled early to isolate myself, to live in loneliness, when I at times tried to forget all this, O how harshly was I repulsed by the doubly sad experience of my bad hearing, and yet it was impossible for me to say to men speak louder, shout, for I am deaf… I must live like an exile, if I approach near to people a hot terror seizes upon me, a fear that I may be subjected to the danger of letting my condition be observed.

He is on the verge of ending his life. But as fate wills, he decides against it. Ludwigs van Beethoven continues to live for 25 years. When he dies in Vienna in 1827, tens of thousands of people attend his funeral.

I would have put an end to my life — only art it was that withheld me, ah it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon me to produce, and so I endured this wretched existence — truly wretched, an excitable body which a sudden change can throw from the best into the worst state…

Produced all that he felt called upon him to produce…and what he produced!

Celebrating Beethoven

We love his music and we need it. As despairing as we may be, we cannot listen to his ninth symphony without emerging from it changed, enriched, encouraged. And to the man who gave the world a gift such as this, there is no honor that can be too great, no celebration joyful enough. It is almost like celebrating the birthday of music itself.

Leonard Bernstein

2020 was Beethoven year, and mankind celebrated (at least as far as Covid allowed) Beethoven’s 250th birthday.

Beethoven is the most frequently played classical composer of all time. His influence seems everlasting. He has been mesmerizing people with the force and beauty of his music and the tales of his personality ever since he lived.

Beethoven is a pop icon more than any other composer from the classical era. He is up there with van Gogh as representing the archetype of the struggling artist on the verge of insanity. The lines quoted above from his 1802 letters contain much of the essence of this image.

But as with many great artists, there are many layers to his work and personality, and there is so much to discover in Beethoven beyond the image of the heroic genius torn apart by cruel destiny.

The Music

I have lived with it, I have studied it, I have rehearsed it over and over again. And I may report that I have not tired of it for a single moment. The music remains endlessly satisfying, interesting and moving. It is not only infinitely durable, but perhaps the closest music has ever come to universality.”

Leonard Bernstein

There is no obvious place to start with the music of Beethoven.

Pieces like Für Elise, the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata, the ninth symphony with the chorale “Freude Schöner Götterfunken” (the anthem of the European Union), and the four tones at the beginning of his fifth symphony are unbelievably famous, and deservedly so. As Bernstein reports, they speak to everyone, young or old, professional or amateur. They have endured for 200 years, and we don’t see them going away any time soon.

One could go at length through his symphonies, be in awe at how Beethoven moves from the constrained classical form of the First and Second symphony on to the revolutionary Third, the Eroica (coincidentally dating from the year 1802/1803, shortly after he decides against suicide), to the Fifth, the Pastorale, the Seventh, the Ninth.

And then there are the 32 piano sonatas, ten hours of densest music that provide an opportunity for a lifetime of study. There are the violin sonatas, the string quartets, Fidelio, the violin concerto, the five piano concertos, etc. The list goes on: there are too many marvels to be found in his works to give them all credit here.

From day one, there is something unique and revolutionary about his music. Nevertheless, I think there is a period where Beethoven peaks, even by the high standards his early output sets. This period is sometimes more difficult to approach than the others, and not as well-known to a general public mostly familiar with his “greatest hits”.

The Late Period

“The form is all. Form means what note follows every other note. And in Beethoven’s case, it is always the right note. As though he had some private telephone wire to heaven which told him what the next note had to be.

It all checks…How he did this, nobody knows. When he composed, he struggled. He scratched out. If you look at the sketches, you see the agonies this men went through. And what has appeared as the final product looks as it was phoned in by God.

Leonard Bernstein

Beethoven’s works are usually categorized into three periods by music scholars: Early, Middle, and Late.

For me and many others, the Late period (1815–1827) is the time when Beethoven creates his most unbelievable, ambitious, forward-looking, transcendent works. This is all the more surprising considering that by 1818, he is almost entirely deaf.

He does not compose as much as he used to. He is bedridden and ill a lot, and the battle for custody over his nephew drags on for years, costing him a lot of money and energy. But in this turmoil, this man finds an inner space, an inner creative force that brings forth some of the greatest music ever composed.

Nevertheless, his late works have not been uncontroversial, and at times they were hardly performed. Complaints about what his music was showing about his mental state had begun at the time of his seventh symphony (Beethoven was “ready for the madhouse”, according to Carl Maria von Weber). The “Grosse Fuge”, maybe the most avant-garde piece of the 19th century, was denied publication as part of Op.127, and Beethoven had to compose an alternative movement. The “Hammerklavier” sonata was never performed and was considered unplayable until Liszt took it upon him to premiere it.

Many thought the deaf guy had gone mad, had lost touch with music that those who could still hear actually wanted to hear. It was difficult music 200 years ago, and it remains difficult to approach to this day.

But that’s all the more reason to approach: because it is so very much worth it.

So without further ado let’s dive straight into three of my favorite examples from Beethoven’s late period (listening recommendations included)!

The String Quartet №14 in C Sharp Minor, Op.131

“After this, what is left for us to write?”

Franz Schubert“…a grandeur […] which no words can express. It seems to me to stand…on the extreme boundary of all that has hitherto been attained by human art and imagination.”

Robert SchumannThe most sorrowful that has ever been said in music.

Richard Wagner

Reference Recording: Alban Berg Quartet

Beethoven’s five Late Quartets and the Grosse Fuge have been considered by many music critics to be one of Beethoven’s crowning achievements. The 14th String Quartet stands out even in this illustrious company: the man himself thought it was one of his greatest, if not his greatest work (although he said that occasionally about the Missa Solemnis as well).

Op.131 is remarkable in every sense of the word.

The expressive range is enormous. The quartet sends the listener on a journey through everything life has to offer, from deepest contemplation to most joyous ecstasy. Bruce Adolphe describes it as taking you from a prayer in church to a dance on the town plaza to an aria on an opera stage to a lecture in a college seminar to a joyful playground, only to end in a dramatic climax in the structure of the old sonata form, as if to take the listener back to the concert hall before being released to ordinary life.

The counterpoint of the opening fugue is dense and can stand its ground when measured against the counterpoint of Bach, who I write about in more detail here (maybe that telephone line Bernstein talked about went straight to Bach’s desk in heaven).

The entire string quartet is, as many of Beethoven’s late works, structurally and harmonically innovative to the point of completely dissolving all of the rules that had defined those of the string quartet of the classical era.

But while it is innovative and daring, it is not for the sake of being innovative. It is not whimsical, or only intentionally so, because it portrays life, and life can be odd and funny and whimsical.

It says everything it needs to say, without a superfluous word spoken. Everything works while nothing could have been expected.

That is for me the true hallmark of Beethoven’s genius, and nowhere does he come so fully to himself as in these late works.

The Piano Sonata №32, Op.111

This is the basic thing about the movement: a simple, unpromising theme, developed via a simple, unpromising heuristic, producing something sublime – big enough to look unmade, unheroic, unpropelled by any sense of human craft or will, even a bit scary.

Ashish Xiangyi Kumar“…perhaps nowhere else in piano literature does mystical experience feel so immediately close at hand.”

Alfred Brendel

Reference Recording: Ivo Pogorelich, Igor Levit (1+2)

What Op.131 is for the string quartet, Op.111 is for the piano sonata.

The sonata is remarkable for more reasons than the Boogie Woogie/Ragtime swing in the second movement. Much has been written about it, and by no less than Thomas Mann, so I will try to be brief. Suffice it to say that the sonata is universally recognized as one of the greatest pieces of piano literature.

It is split into two movements, which is in itself very atypical for a sonata. These movements form a stark contrast: the first is dramatic, virtuosic, dark, worldy, in a minor key. Just listen to the first chords and you can guess what is coming.

The second movement is something else. It is simple, in the major key, contrasting the first movement. A variation on a theme. The variations follow from one another based on a simple rhythmic idea.

It sounds more straightforward than it is, for the range of musical expression that follows from it is incredible.

From the theme emerges a farewell, a transcendence, a mystical experience that can not be described by words. As Wittgenstein said, mysteries are there to be deepened, so the best thing is to let the music speak for itself. The final struggle of man is metaphysical, and I think no artist ever captured this struggle more directly than Beethoven.

The Diabelli Variations

“Beethoven here shines as the ‘most thoroughly initiated high priest of humour”

Alfred Brendel

Reference Recording: Anderszewski, Schnabel

Last but not least, we have to talk about the Diabelli variations.

Austrian composer Diabelli sent out a theme to all the major Viennese composers of the time in order to compile a set of variations reflecting the spirit of Austrian music at the time.

When Beethoven received the theme, he thought it mediocre and downright refused to write a variation on it.

But then he thought about it again and wrote 33.

The work is, therefore, ironic from its very conception. In some variations, Beethoven is obviously making fun of the shortcomings of the theme. In a sense, he is showing off his prowess: what he manages to make out of a weak theme is without compare.

Pathos is not everything that makes up Beethoven’s music. Humor is a big part of it from the beginning (Martha Argerich talks here about the sense of humor she discovered in Gulda’s renditions of Beethoven’s early piano concertos). Or think of the rage over a lost penny, which he also wrote at the end of his life.

No one alive could have pulled the Diabelli Variations off, and Diabelli himself writes “We present here to the world Variations of no ordinary type, but a great and important masterpiece worthy to be ranked with the imperishable creations of the old Classics — such a work as only Beethoven, the greatest living representative of true art — only Beethoven, and no other, can produce.”

The Diabelli Variations are a microcosm of Beethoven’s art, his unending creativity, of his absolute mastery of the piano and music itself.

Celebrating Beethoven

“Music is a higher revelation than all wisdom and philosophy. Music is the electrical soil in which the spirit lives, thinks and invents.”

― Ludwig van Beethoven

Besides these two pieces, the late period also provides many other treasures: all his late string quartets and late piano sonatas, the Missa Solemnis, and of course the Ninth Symphony. And not to neglect his earlier works. They too deserve to be celebrated and listened to.

I hope this gave you some incentive to go out exploring Beethoven (and classical music in general, as I write about here).

There is always something fresh to discover. One can always emerge changed, enriched, encouraged.

Let us celebrate because there is no celebration joyful enough. Let us celebrate the birthday of music itself.

About the AuthorManuel Brenner studied Physics at the University of Heidelberg and is now pursuing his PhD in Theoretical Neuroscience at the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim at the intersection between AI, Neuroscience and Mental Health. He is head of Content Creation for ACIT, for which he hosts the ACIT Science Podcast. He is interested in music, photography, chess, meditation, cooking, and many other things. Connect with him on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/manuel-brenner-772261191/