Traditionally, human beings are said to have five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch.

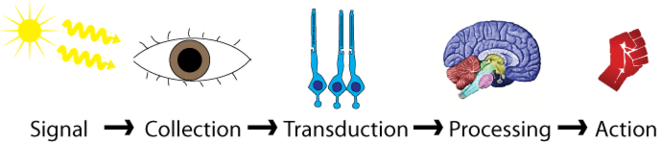

Our senses bring us into contact with the outside world. All we know about the world has to come in through our sensory organs before it can be processed and made sense of.

Our senses have developed to serve an evolutionary need. While in our fishy ancestral times, we spent our days underwater, not being able to see very far around us, eyesight improved dramatically on land to deal with the constant threat of snakes and the likes slithering into our field of vision, threatening to eat our babies while being very hard to discern against the backdrop of rainforest floors. Our ears developed to sense small vibrations in the air that could have been caused by a predator coming for us, and later down the road could pick up on subtle alterations in another human’s voice, helping us to navigate the complex and intricate net of interhuman social relations.

As our senses have developed to serve an evolutionary need, and evolution needs to be quite frugal with her resources, our senses are limited in their range of applicability and specialized for specific tasks: bats use ultrasonic sound to create a mental representation of the dark spaces surrounding them, while whales sing their calm songs to communicate fitness to potential mating partners across the oceanic boundlessness of the deep sea. Both skills wouldn’t be particularily useful for human beings hunting across the savannahs of Africa during daylight and sitting around fires telling stories by night.

Evolution is always concerned with filtering out all information that we can afford not knowing about, and so we only pick up a tiny slice of what is happening around us, missing out on a substantial amount of information about the world.

This has been the state of affairs for countless years, and nature figured it was alright like that. But as the particular subtype of the great apes that we are a part of has certain eccentric habits and interests, we have been slowly expanding the range of our collective senses.

While there is information we can afford not knowing about, we are just too damn curious to handle not knowing about it.

And so while our ancestors were happily constrained to electromagnetic waves in the rather narrow optical wavelength spectrum in the range of 400–800nm, with the help of modern technology, our phones allow us to tap into and process the information encoded in the pulsing of WiFi routers, and radios and radio telescopes have both allowed us to broadcast the newest billboard charts across continents and to make sense of the intricacies of the patterns in the cosmic microwave background.

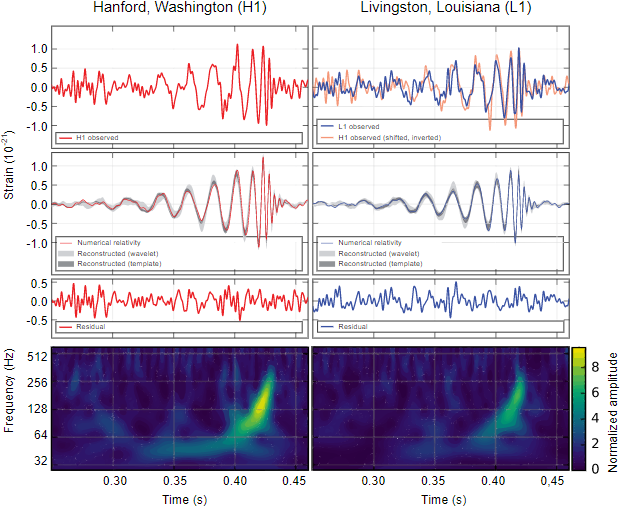

In recent years, humans have even discovered an entirely new sense: in 2016, the LIGO project first detected gravitational waves. There is really nothing substantially different between LIGO and our eye: both pick up on subtle vibrations of the force fields that constitute physical reality, with the first specializing on electromagnetic waves and the latter focusing on their gravitational counterpart. But an eye or an ear certainly wouldn’t have done the job that LIGO achieved: in order to discern the minute vibrations in the fabric of space-time itself, the ingenious engineers of the detector needed to build two four-kilometer long tunnels whose length modulations on the scale of one ten-thousandth of a proton in diameter could be measured.

This is only one of many impressive feats of modern physics, with us finally sensing the Higgs field permeating the universe only four years before beginning to detect gravitational waves. We can only wait to see what the future will bring, and how far we can push the boundaries of what is observable to us.

But this is only part of the story. For while we have discovered how to expand the range of our senses far outside of our body, we are also beginning to expand them on the inside.

The body is frail, and its senses are easily lost. A loss of senses cuts us off from the world. Familiar voices and faces are never seen again.

When Beethoven lost his hearing in his late twenties, he was quite desperate(much more on this in my article A Deaf Guy Gone Mad), and even considered taking his life. A musician that couldn’t hear was completely out of touch with participating in the communal aspect of making music together. In a desperate attempt to get auditory information into his brain, “Beethoven found a way to hear the sound of the piano through his jawbone by attaching a rod to his piano and clenching it in his teeth”.

While Beethoven’s fix was rather rudimentary and could never restore him the pristine hearing of his adolescence, the advances of modern science have allowed us to make voices and melodies that were deemed lost heard again in new, more sophisticated manners.

David Eagleman’s startup company NeoSensory is developing a device called Buzz, which is essentially a buzzing wristband that is equipped with a microphone. It records the sounds from the environment and translates it into buzzing patterns on the wrist of the person that wears it. This way, auditory information gets into the person’s brain without having to rely solely on the person’s ears. It’s kind of like Beethoven’s stick, but much more technologically advanced.

And while it might seem puzzling that a person wearing a wristband giving off specific buzzing patterns could start making sense of them, the brain is actually really good at this: an important aspect of explaining why it is revolves around the concept of neuroplasticity.

In Norman Doidge’s book The Brain That Changes Itself, he describes the case of a patient who was suffering from extreme cases of dizziness and vertigo caused by damage to the vestibular system that keeps our lives literally in the balance. Whenever she stood up, she felt like falling over, like the world was toppling beneath her legs. Her problem was not overcome by a complicated procedure painstakingly restoring the damage done to the vestibular system, but by a device that mapped information about the position of her body in space to a signal on her tongue. And while initially, she had a hard time making sense of the fizzling in her mouth, her brain began to use the information to reclaim her balance.

Her brain slowly rewired itself and mapped information coming in through new pathways onto old brain regions. Her brain started to make sense of the input it was provided with, and consecutively helped her find her way back to a normal life.

The basic architecture of the brain is probably much less specialized than we initially (more in my article on Why Intelligence Might Be Simpler Than We Think). People born deaf learn to communicate via sign language, remapping their linguistic abilities and brain regions responsible for language processing like the Wernicke and Brodmann areas to make use of visual information instead of auditory one. The brain processes information: the pathway the information uses to get into the brain is open for change, and the neuroplasticity of the brain means it’s pretty good at making the best use of what is thrown at it.

New technologies are oftentimes born in a scientific or medical context, and this is usually where they have the potential to alleviate the most suffering. Giving deaf people the ability to hear back can improve their lives dramtically. What Beethoven dreaded most when he turned deaf was the isolation springing from the inability to communicate with his fellow men, something that was to haunt him for the rest of his living days.

But often enough new technologies show a potential that goes beyond the purely medical to something that is driven more by our ape brain’s endless curiosity. Many times they have the potential to change the way we perceive the world and think about the world.

The premise of the feelSpace belt is simple: it is a belt worn around a person’s belly that subtly vibrates in the direction of the magnetic north. At a recent neuroscience conference I was attending, a philosophy professor that had worn the feelSpace belt for a period of six weeks shared his experiences.

He said he was surprised how quickly he integrated the experience of the belt into his daily experience and, really, into his world view. It was as if he suddenly had a new sense that felt completely natural and integrated, as if he had had it since birth. It changed his view of reality: he started to dislike traffic lights, because the moment they switched, they sent out a weak magnetic pulse that he perceived as his whole world shifting. When he was wearing the belt, he started to dislike city life in general, with all its distracting, confusing electromagnetic debris pulsing around him, and began longing for the quiet of the countryside more frequently.

And for the first time in his life, he noticed the peculiar fact that all his favorite toilets were pointing north.

According to Wikipedia, “Art refers to the theory, human application and physical expression of creativity found in human cultures and societies through skills and imagination in order to produce objects, environments and experiences.”

A movie is an experience, a piece of music is an experience. Even a sculpture and a painting, albeit they have a more static, permanent reality, only come to being as art through the experience and interpretation of them.

Art is the complex play of reality with our senses. As we are slowly expanding the range of possible objects, environments, and experiences, so does the range of possible art grow. And what more to expand the range of possible objects, environments, experiences than entirely new ways of sensing the world?

The reality of the sciences is that of a boiling soup of vibrating fields and molecules, forming an infinite array of possible signals to be picked up and processed. The electromagnetic spectrum alone is in principle infinite, and the range that is populated by meaningful signals is billion times that of the range we can perceive with our eyes.

What if we could hear tones that were deeper than anything we had ever heard, or higher? What if we could translate sounds into sights, and sights into music? What if we could smell like a dog one day, or hear like an owl? How would that change which people we liked, which places we went to, what things we did in our free time? What works of art we would create?

Neuralink’s brain-computer interfaces are much-discussed these days, and these interfaces are a technological development that will probably have a large influence over our future. But as David Silverman points out, before we develop fancy devices that can directly alter the activity of our brains, why not take a more pedestrian approach and start with what we already have: the skin on our wrists or the tip of our tongues.

Art will change because the way human beings interface with reality will change, and is already changing. It is fascinating to think about not only where science and technology are headed, but how they bring so many products of culture along with them on the ride, the products of beauty that shape our experience of reality and give it meaning. The art of the future will be different. But it’s surely something to look forward to.

About the AuthorManuel Brenner studied Physics at the University of Heidelberg and is now pursuing his PhD in Theoretical Neuroscience at the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim at the intersection between AI, Neuroscience and Mental Health. He is head of Content Creation for ACIT, for which he hosts the ACIT Science Podcast. He is interested in music, photography, chess, meditation, cooking, and many other things. Connect with him on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/manuel-brenner-772261191/