People don’t have ideas. Ideas have people. — Carl Jung

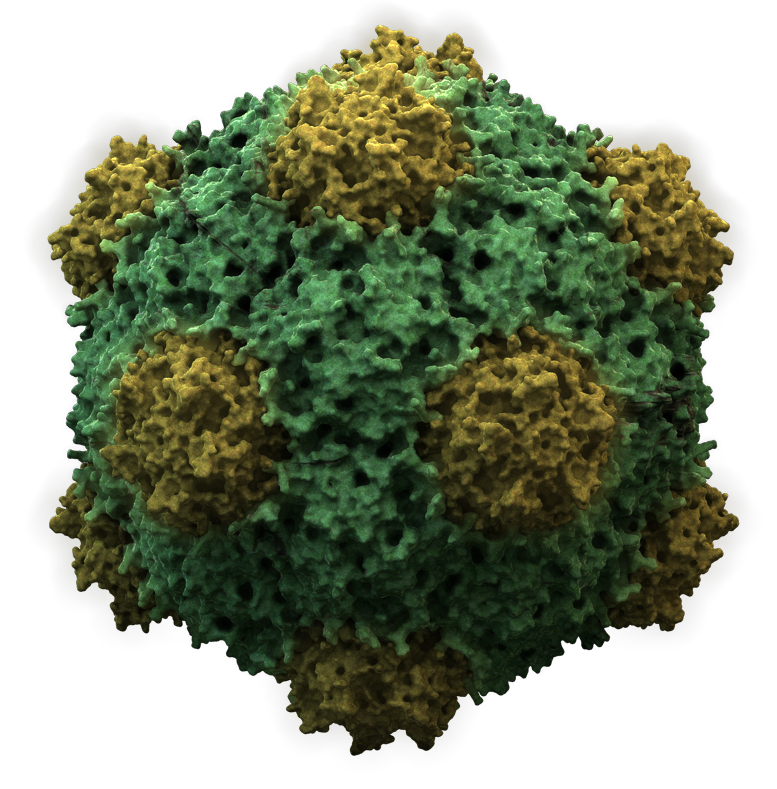

A virus is an infectious agent that replicates in the living cell of a host organism. In a sense, a virus in itself is not alive. It instead relies on living hosts to do all the work for it, making it, sometimes unbeknownst to the host, reproduce and spread.

An idea can be thought of as a little cell of meaning, of intellectual content, that lives in the shared intellectual and cultural space of a society or a species.

In itself, an idea is even more lifeless than a virus. Life is only given to it through the hosts it populates.

It can be difficult to properly mark out what an idea is, to find a clear definition that satisfyingly captures its essence (e.g. how would you define love?). An idea can be communicated in different languages, in the space of signs and emotions. It might be expressed as a mathematical formula. Nevertheless, an idea points somewhere, to something beyond its idiosyncratic representation, to an abstraction behind every concrete instantiation. Humans have grappled with the ontological status of ideas for a long time. The idea of the reality of ideas is almost as old as philosophy itself: in Plato’s conception of existence, the realm of ideas transcends the realm of things and is even more real than the material world we inhabit.

In more modern parlance, an idea might be likened to what Richard Dawkins, explicitly inspired by the genes of our genetic machinery, coined a “meme”: a unit of cultural transmission, a carrier of meaning that allows for self-replication, transmission, and mutation. Ideas arise from the coupled dynamics of billions of neurons that make up our brains, arise in the coupled dynamics of billions of human brains across thousands of years. Ideas inhabit this complex ecosystem somewhere between the individual firing of neurons and the collective consciousness of nations. From a physics perspective, we could call them emergent properties of complex interacting systems (I discussed a similar idea in my article on the Thermodynamics of Free Will).

And while our genetic and physiological makeup has not changed substantially in the past hundred thousand years, our lives have been transformed radically. The values we hold, the way we live, the way we organize our relationships, our ideas about the world have changed drastically. Our hardware is the same, and many argue that a child born

50 000 years ago could easily be raised in our modern societies.

But our software has changed dramatically.

The life of ideas

The power of new software to grasp our imagination and transform our actions should give us pause: who is developing this new software, and who determines which software survives?

The DNA of a virus and its surface proteins reveal something about the hosts it is most likely to inhabit. When a virus mutates to become more infectious, it does so by implicitly selecting for the peculiar vulnerabilities of its host. And every time a virus spreads to a new host, it gets another chance at mutating to make it spread even more effectively.

Humans for the most part think of themselves as rational beings. We come up with ideas, and we can employ our faculties of reason to judge their quality, to consciously select good ideas that survive and bad ideas that get discarded.

But it might not be just as easy.

The shape of ideas that exert most power over us reflects who we are, for better or worse. Ideas can take control of us. They can appeal to the darker angels of our nature in ways we don’t always consciously understand: bad ideas can induce mass delusions, hate, genocide.

Infectious ideas

During World War One, the idea of communism was, by distributing leaflets, planted in the enemy’s front line. Much like a virus, it was supposed to weaken morale and encourage mutiny. The German military leadership around Ludendorff arranged for a train to ship Lenin from Switzerland to Russia in order to “infect” all of Russia with Communism. Marx and Engels themselves realized the power of this idea that was in the air when in the opening lines of the Communist Manifesto, they wrote: “ We are haunted by a specter, the specter of Communism”.

Human beings are complex, multi-layered beings, and in the same way, ideas can be multi-layered and complex, operating on us on multiple layers.

Jonathan Haidt investigated how our disgust sensitivity shapes our moral judgment: he concluded that the Nazi ideology actively appealed to some of the older parts of the human brain responsible for regulating disgust and cleanliness, and did so with horrifying power. When the Nazi propaganda likened Jews to parasites, spoiling the purity of the Volkslörper (literally the body of the German people), this mapped the idea of the cleanliness of the Arian race right onto brain areas that were originally devised by evolution to protect us from germs. In private correspondences, Hitler frequently used metaphors derived from cleanliness when talking about Jews.

Dangerous ideologies are precisely so powerful because they tend to expose specific vulnerabilities of our brains: ape-brains that have become a little too intelligent for their own good.

What are the conditions for ideas to spread?

A couple of years ago a friend told me about a game at a party. The rules for this game are simple.

If you think of the game, you lose. Then you have to tell everyone around you that you just lost the game. When they ask which game you are talking about, you have to tell them about the game. When they, in turn, think of the game, they have to tell everyone around them that they just lost at the game.

Who came up with this game? I didn’t. Someone told me about it when he had lost the game. Did he come up with it? He probably didn’t.

But now I know the game and you know about it as well.

This might sound silly, but it’s actually a beautiful example of an idea that has built into it a mechanism that makes it spread: it is explicitly self-perpetuating.

How well the idea of the game spreads depends on a lot of factors. What motivates me to abide by the rules of the game, and to actually tell you each time I have lost? What motivates you, in turn, to spread the game among your friends? The comedic effect plays a role. There’s something entertainingly pointless about it that works well with the self-deprecating cynicism that a lot of human beings find funny for some reason. Now I was motivated to talk about this game from a meta-perspective: not as a game itself but as an interesting structure in the space of ideas.

Systems of ideas that spread easily incorporate incentives for their spreading into themselves. Communism as a political ideology is built around the call for world revolution. The world’s biggest religions all in some way address the responsibility of the believer to convert others around him, many having the explicit goal of converting the entire world.

Otherwise, you probably wouldn’t have heard of them.

Ideas have people

Humans write their history of ideas as that of great thinkers. We talk about Plato and Aristoteles, Copernicus and Newton, Darwin and Wallace, Marx and Engels, Buddha and Jesus Christ. The ideas of these thinkers have drastically changed the course of history, and the way we look at the world. But in which sense can they be credited for coming up with their ideas? Ideas fight their own evolutionary struggle against other ideas. When you look at history it almost feels like an idea can be hanging in the air, just waiting to be thought.

Newton and Leibniz stand for one of the most groundbreaking inventions in the history of mankind: calculus. But they also remind us of the undeniable fact that the foundations of calculus were conceived of by two people independently at the same time. Somewhat ironically, they would end up fighting ferociously about who would get credit for it.

This phenomenon occurs very frequently in science philosophy and the arts. During the Cold War, a great many new theories discovered by the Americans were also discovered by the Russians at approximately the same time, without any side having knowledge of the other.

Maybe we overestimate the role of great thinkers: maybe they were just at the right place at the right time.

Developing resilience

There are many dangerous ideas floating around in our world, especially in our information age when the next idea is always just around the corner.

Ideas can make people do horrible things. I think one of the most important insights to be gained from this shift in perspective is to start distinguishing between bad ideas and bad people, between bad ideas and people especially vulnerable to these ideas.

It’s easy to blame people for believing in certain things, be it in the righteousness of genocide or in the superiority of a certain race. It‘s more challenging, but can be illuminating, and ultimately much more fruitful, to look at the epidemiology of the idea: to see why it has the power to spread and infect.

To see how it has mutated to enchant us, to seduce those most vulnerable to its influence: and to build ourselves and our institutions to be more rational, critical, and resilient to the influence of bad ideas trying to infect us.

About the Author

Manuel Brenner studied Physics at the University of Heidelberg and is now pursuing his PhD in Theoretical Neuroscience at the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim at the intersection between AI, Neuroscience and Mental Health. He is head of Content Creation for ACIT, for which he hosts the ACIT Science Podcast. He is interested in music, photography, chess, meditation, cooking, and many other things. Connect with him on LinkedIn at https://www.linkedin.com/in/manuel-brenner-772261191/